Gaming the Reader: An Argument for Surrealist, Dialogic Composition

By Allen C. Jones

“Poiesis, in fact, is a play-function.”

—Johan Huizinga in Homo Ludens

At a recent festival, a writer claimed he didn’t think about his reader. I just tell the story, he said. I understand the allure of writing as self-expression, and if the story you have to tell challenges nothing in the listener, then I suppose you don’t have to think about them. But what if it does? What if you are not preaching to the choir?

Think of Calvino’s brilliant Invisible Cities, where Kublai Khan asks Marco Polo to describe his empire. The empire is so vast that the Khan can no longer wrap his mind around the fact that it is his. So, he asks the traveler to wrap his words around the world and deliver as one might deliver a package.

The Khan’s desire, as Laurence Breiner points out, is much like that of a traditional reader, hungry for the empire of words we call a story to “make sense.” Most of us read with a very certain hunger for the pieces to come together on that last page.

But what if that last page knocks us off the throne? What if a story actually challenges us?

People say that America is a very divided place. Some people love Trump. Others hate him. This means any story including Trump, or the values he represents, will be read radically differently by these two audiences. Can I write a story like this and not consider my audience?

On my first book tour, I learned to package a novel that took me seven gut-wrenching years to write into twenty seconds of “what’s hot”: apocalypse, speculative cli-fi, magical realism, strong female character, coming-of-age. I was like Marco Polo, trying to reduce the empire down into a few soundbites to make the emperor’s eyes light up and take out his wallet.

Wolfgang Iser has an idea called the “implied reader” which refers to the assumptions the text makes about its reader. For example, if I mention Trump, and my implied reader is liberal, I expect her to scowl. But what if I want this liberal woman to realize that Trump, like her, is quite human. This is hard if she is plugging her ears.

On my book tour, I met my reader. I traveled across two continents and visited over fifty bookstores, and I discovered this reader to be nowhere near as diverse as the implied reader I had been addressing. They were far too much like me.

I would start a character and immediately I would see my implied reader shaking their head in disgust. Oh yeah, they would say. I know that guy. But I wanted to push my reader out of their comfort zone. I wanted to give them a beer with this guy they hated and have them enjoy it. I wanted them to slowly realize who it was and do a double-take. I wanted to wake the reader up to the fact that those people across the line were a lot like them. And the truth is, as cozy and wonderful as that sounds—we’re all connected—such a realization is actually quite uncomfortable.

Looking back at the stories that became Big Weird Lonely Hearts, I see that rather than aiming to tell a story, I was aiming to do precisely this. I wanted to lure them in slowly. I wanted to put a fluffy puppy in their laps and then have them look down and realize it was a snake. Oh my god, I hoped they would say, I’ve been having a beer this whole time with that asshole! Shit! Even worse, I kind of like him!

Around this time, I was designing three-dimensional texts on the computer. Originally, I had wanted to invent a simple way to track the connections in Virginia Woolf’s The Waves, a book with almost no plot that’s basically impossible to read. To do this, I had ended up building word clouds coded by color so that a reader could explore the book through the connections between words that in the traditional paper text were quite far away from each other. It was basically a way to make concordance work more efficient and interactive.

But here was the problem. With regular texts, we have basic reading rules: left to right, check your socials, yawn and count how many pages left, continue. When people approached my 3D word clouds, they had no idea what to do.

As I struggled with usability, I ended up attending a research summer where I was introduced to game design. And what are games but a set of rules? And what did I need? Rules!

Since then, I’ve been working on setting up non-traditional reading interfaces that use gamification as an engine (see my Dylan Thomas Domino game: http://www8.uis.no/fag/DigitalGamesForReadingLiterature/www/docs/). Originally, this was meant as a teaching and research tool, but game-thinking was like an invasive species, creeping into all of my thinking, even my creative work.

An example of this is a long, game-based piece I wrote for Mudlark.

Rules:

- Watch the news in Norwegian.

- Write down phrases that seem interesting or useful.

- Take the list of phrases and mash them up.

- Try to “make things happen.”

As I attempted to “make things happen,” I found my compositional method driven by Bakhtin’s notion of dialogism.

Bakhtin argues that social groups speak in different ways. I say, “dude that was killer,” because I grew up in the eighties in northern California. Norwegians say, “There’s no such thing as bad weather,” because bad weather is all they have. Etcetera.

Here is one of the couplets this method produced:

After Christ left the restaurant,

there was a preoccupation with end times.

This takes the way we talk about famous people—apparently, we care when they leave a restaurant—with our preoccupation in the US with end times. It was socialites versus end-timers. And it was the crease between the two, what Susan Laxton calls “the fold” in Surrealist works, that created the spark in the piece.

In essence, the game was to push the reader from one speaking group to another with the juxtaposition creating humor, social commentary, etcetera.

You can see the full result published here: https://www.unf.edu/mudlark/flashes/jones.html

After writing that piece, I realized this method was a microcosm of what I was starting to do in fiction. The difference was that it was the reader I was attempting to fold my words against. This, of course, is nearly impossible, but if my implied reader is an American, and America is truly divided, this presents a very interesting fold to navigate along and against.

At the very least, it gave me an entirely new way to think about the central engine in my fiction.

I have to go shovel snow now, but I’ll leave you with this. I believe I have discovered a rather interesting connection between dialogism, Surrealist juxtaposition, gamification, and what drives a text. I will sum it up by dialogizing William Carlos Williams’ voice with my own:

This is just to say

I have written

these stories

for someone else

inside you

and whom

you were probably

trying

to avoid

Forgive me

they were hungry

and you had

all the food

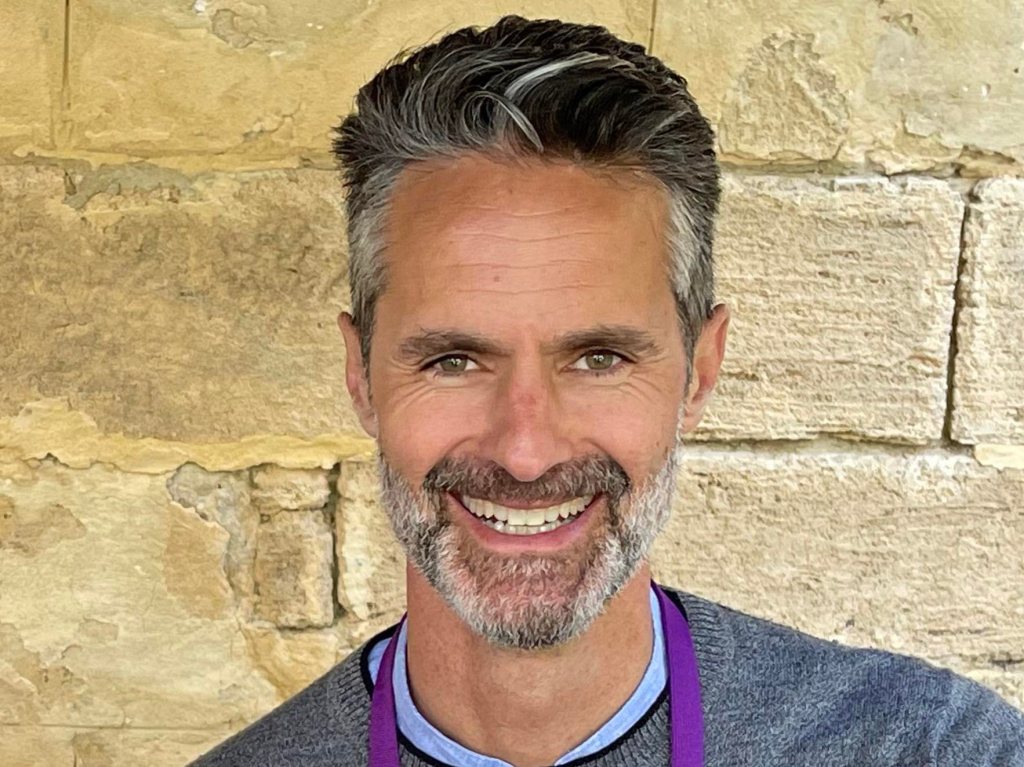

AUTHOR BIO

Allen C. Jones received an MFA in poetry from the University of New Mexico and a PhD in English from University of Louisiana. He serves as associate professor of literature and culture at the University of Stavanger, Norway. His work includes a novel Her Death Was Also Water (MidnightSun), a poetry collection Son of a Cult (Kelsay Books), and a story collection, Big Weird Lonely Hearts (forthcoming). Find links to his work: allencjones.com. Follow him on socials: allencjones_theauthor